Padre José María Morelos's orders were clear. All he had to do was travel back into south of Mexico and raise troops for the Army of America; then take the city of Acapulco. He was also to disrupt the trade routes. New Spain's economy was did very well out of commerce with the Philippine Islands. If that was to stop, then the viceroy would lose a lot of funds. Ok. Morelos leapt back onto his horse and rode away.

Padre José María Morelos's orders were clear. All he had to do was travel back into south of Mexico and raise troops for the Army of America; then take the city of Acapulco. He was also to disrupt the trade routes. New Spain's economy was did very well out of commerce with the Philippine Islands. If that was to stop, then the viceroy would lose a lot of funds. Ok. Morelos leapt back onto his horse and rode away.Morelos had an impressive résumé. His dad was a carpenter, so Morelos had picked up some of the skills of that trade as a child. He was physically fit and strong. Years working with his back to the sky in the plantations had seen to that. He was a man of letters. He'd been an accountant. He'd organized the administrative side of a large hacienda. He was an scholar, with degrees under his belt. He was a man of vision and design. He'd overseen construction work. He was a great priest. None of which precisely amounted to any military experience at all.

He had followed Padre Miguel Hidalgo's academic route into the priesthood. The Roman Catholic seminaries and universities had been great for learning about theology; but they had been woefully lacking in classes on warfare, battlefield strategic thinking and the practicalities of leading an army. Up in the north, where Hidalgo himself was the general, this ommission was distrastrously telling. He had been forced to give up command of the army to Allende and Aldama - two military men, who actually knew what they were doing.

Down in the south, Morelos was having none of that trouble. For years, he had been inspired by Hidalgo to reach beyond himself. He could be whatever he wanted to be. It never crossed Morelos's mind that he didn't have the skill to lead an army. If Hidalgo was doing it, then so should he. Morelos knew that he was a clever man, all he had to do was apply himself to the job in hand. The difference between himself and Hidalgo, so it transpired, was that Morelos was a natural. He proved to be a talented strategist. His prowess turned out to be so great, that he has gone down in history as one of most outstanding military commanders of the War of Independence.

But that was all in the near future. For now, Morelos returned home, to his family in San Agustín, Carácuaro, and set about forming his own troops. He was still the parish priest there; however, only 25 men signed up to join him. Undaunted, Morelos led his small party across Michoacán state, drumming up support and boosting his numbers. By the time he'd been through Nocupétaro, Cuahuayutla and Zacatula, it was all looking a bit more respectable. He even had weapons.

'Weapons' might be stretching the definition of the word to breaking point. As with the northern Army of the Americas, what most of Morelos's troops were armed with was the tools of their trade. They were largely drawn from the fields and workshops, carrying their own machetes, scythes and axes. There were a few guns, but nothing to those available to the fully army and trained Realistas (Spanish Army in Mexico). It wasn't until Morelos led his army into Guerrero, gaining recruits there, that he came into possession of his first cannon. They called it El Niño.

It was during this initial call to arms that Morelos was joined by Nicolás Bravo Rueda. Better known as just Nicolás Bravo, this idealistic 23 year old was a native of Chilpancingo, Guerrero. He had arrived with his father, Leonard, and his brothers, Max, Victor and Miguel, as soon as the recruitment drums had sounded in their area.

It was during this initial call to arms that Morelos was joined by Nicolás Bravo Rueda. Better known as just Nicolás Bravo, this idealistic 23 year old was a native of Chilpancingo, Guerrero. He had arrived with his father, Leonard, and his brothers, Max, Victor and Miguel, as soon as the recruitment drums had sounded in their area. Their arrival was significant. Leonard was a wealthy plantation owner - the vast Chichihualco farm, in Chilpancingo, belonged to him - and the whole family were Spanish Creole. They represented the very class of people whom the insurgents were fighting, but politically, the Bravo family were right on side. Leonard Bravo was instantly put in charge of a portion of the fledgling army.

By December, 1810, Morelos declared himself ready to move onto the second part of his orders - capture Acapulco. Acapulco, at the time, was a Spanish stronghold. It governed much of the trade into Asia and was protected by the imposing San Diego Fort. The Realistas within it also knew that Morelos was coming. Under the command of Francisco Parés, the Realistas rode out to meet the insurgents, confident of a swift victory. They were wrong. Morelos's leadership was so inspired, and his strategy so sound, that the Battle of Tres Palos resulted in a resounding victory for the rebels.

San Diego Fort

Morelos moved on into Acapulco itself and instructed his troops to burn the city down. Much of the population was already inside San Diego Fort, with what was left of the Realistas. This proved impregnable to the insurgents, but they could lay siege to it. This was precisely what they did. With no food or other supplies able to enter the fort, the inhabitants were soon struggling. It took nearly two months for Realista reinforcements to arrive. When they did, they were numerous enough that Morelos was forced to move on.

He hadn't been idle during the seige though. Leaving just enough people to ensure that San Diego Fort was isolated, Morelos had led the rest of his forces on lightning raids into the surrounding towns and villages. The majority of coastal towns of Michoacán and Guerrero were now under his control, all of them denying access to the Pacific Ocean for the viceroy's traders.

News trickled down to the south. Hidalgo, Morelos's hero and mentor, had been arrested, along with all of his high-ranking commanders. With the main Army of the Americas now in disarray, that left the whole insurrection without a leader. Morelos had always followed Hidalgo. Now he was the esteemed padre's successor, in the War of Independence. So be it. This was not the time to give up.

The victories went on. Within nine months, Morelos's army had been involved in 22 battles and had won them all. He had even taken the cities of Chilpancingo and Tixtla. As Allende, Aldama, Jiménez, then later Hidalgo, were being executed in Chihuahua, right up in the north, the whole south-west was rising with the rebels. As more people joined them, more places were taken.

Morelos's Campaign Trail

It wasn't just the south-west. Nicolás Bravo had ridden north with his commander, Hermenegildo Galeana. They were responsible for the skirmishes breaking out all over Veracruz state during 1811. By 1812, they were gathering in strength and support.

Early in the year, in the port of Veracruz, they nearly succeeded in overthrowing the Spanish governors. As a result, the viceroy had to send many Realistas there, in order to keep the sea link open with Spain. They were successful (until 1820), but that diverted the Spanish troops away from other areas in the state. Galeana and Bravo quickly took advantage of this. Very soon, they had taken the major Veracruz cities of Ayahualulco and Ixhuacán, as well as most of the state itself. Now fearing for Veracruz's capital city, Xalapa, the Realistas had to flee the port to defend it.

Back in the south-west, Morelos's insurgency seemed unstoppable. Then came Cuautla.

The city of Cuautla had put up a fierce defense, but Morelos's strategies had won through. The insurgents entered the city on February 19th, 1812. But there they were forced to stay. The Realista general, Félix María Calleja, had rallied his own troops and surrounded them. This was the same general who, two years before, had defeated the Army of the Americas, at Calderón Bridge. He was a brilliant military strategist. Morelos had found his equal.

But not quite. For 72 days, the siege held. Calleja was rigorous in maintaining his circle of highly disciplined soldiers. He didn't just stop supplies getting in, but also kept the city under the constant bombardment of artillery and cannon fire. Nothing that Morelos tried could break their strangehold on the city's perimeter. By late April, the population and troops, imprisoned inside the walls, were reduced to eating cats, rats, and lizards. When they couldn't be found, then it was snails or grasshoppers. However, it was also a stalemate, because Calleja could not break into the city.

Then, on May 2nd, 1812, Morelos tried something new. He simply left the city. It was in the early hours of the morning, when the army, with a handful of civilians, quietly crept out. Silently praying to God, the Virgin of Guadalupe, and anyone who'd listen, they sneaked past the night-watch and made it safely into the countryside.

Then, on May 2nd, 1812, Morelos tried something new. He simply left the city. It was in the early hours of the morning, when the army, with a handful of civilians, quietly crept out. Silently praying to God, the Virgin of Guadalupe, and anyone who'd listen, they sneaked past the night-watch and made it safely into the countryside. Calleja was furious, when he discovered them missing, later in the morning. He sent his army after them and managed to engage them in battle. But weak with hunger and out-numbered, Morelos ordered his army to disperse. They did so, individually, in twos or in small groups, regrouping further on. Calleja was incensed, but with the rebels scattered to the wind, he couldn't do much about it. He returned to Cuautla and burned it down, then ordered his army to march back to Mexico City. There he claimed a hollow victory.

Morelos, meanwhile, waited for them to leave, then returned to Cuautla. Now it was firmly in the hands of the insurgents. With his army swelling again, he was able to divide it further, under the leadership of able men. Nicolás Bravo and Hermenegildo Galeana had returned for the fight at Cuautla. Bravo had acquitted himself so well, that Morelos had given him his own forces to command. He'd used them to Calleja, during the siege, when it seemed that the Realistas actually would break through. Now he used them to return to the north-east and to continue to harry the Realistas there.

Another man had proved himself at Cuautla. This was a Roman Catholic priest, from Mexico City, named Padre Mariano Matamoros y Guridi. Padre Matamoros had sympathized with the rebels from the beginning. He was so outspoken in these sentiments that, in 1810, the Spanish authorities had had him jailed. He had managed to escape from prison, a year later, and had made his way to Morelos. At 41 years old, he had joined the Army of the Americas.

Another man had proved himself at Cuautla. This was a Roman Catholic priest, from Mexico City, named Padre Mariano Matamoros y Guridi. Padre Matamoros had sympathized with the rebels from the beginning. He was so outspoken in these sentiments that, in 1810, the Spanish authorities had had him jailed. He had managed to escape from prison, a year later, and had made his way to Morelos. At 41 years old, he had joined the Army of the Americas. After witnessing Matamoros's skill at Cuautla, Morelos had no hesitation in promoting him to lieutenant general. This effectively made Matamoros the second in command of the whole insurgency.

For the next 18 months, the rebels moved through the south of Mexico. Victory followed victory. They returned to Acapulco and this time managed to take it. Better still, they secured Oaxaca, which was the richest, most populated city in the southern region. From Veracruz, in the north, to the Pacific Ocean in the south, the land was under the control of Morelos.

On September 13, 1813, in Chilpancingo, Padre Morelos read out their declaration of independence. It was entitled Sentimientos de la Nación (Sentiments of the Nation); and its signatories proclaimed themselves the government of an independent Mexico.

Morelos was their president, but he disdained any high or mighty titles for himself. After several suggestions were presented to him, Morelos chose one for himself: Siervo de la Nación (Servant of the Nation). He busied himself, and his administration, with debating several laws, in addition to the 23 points laid out in the declaration.

Statue at Chilpancingo

But then, after that, it all went wrong. Morelos attempted to take his home city of Valladolid, on December 23, 1813. It failed. Worse still, Matamoros was captured. Morelos offered 200 Spanish prisoners in exchange for him, but was turned down. Padre Matamoros was defrocked, excommunicated and tried for treason. He was executed by firing squad, on February 3, 1814, in Valladolid's central plaza.

The insurgents were to win no more decisive battles after that. Morelos tried, but his strategies weren't working out as they once had. By late 1815, his own government voted to strip him of some of his powers on the battlefield. He accepted the decision graciously. But then bad luck turned to catastrophe.

On November 5th, 1815, Morelos was escorting a party of his Congressmen through Tezmalaca, Puebla. Matías Carrasco had once been an insurgent, but he'd swopped sides and was now on patrol at the helm of a troop of Realistas. He knew exactly who Morelos was, when he saw him. Morelos was out-numbered. He only had 200 men with him. Carrasco swooped down and the ensuing battle was very quick. The outcome was inevitable from the start. Morelos was arrested, along with all of the rebels with him.

Morelos watched, as 150 of his men were executed by firing squad, in front of him. The remaining 50 were chained and sent to Veracruz. There, they were told, they would be sent to Manila and sold into slavery. Morelos was taken, in chains, to Mexico City. He was tried and found guilty of treason. But the Inquisition also wanted him.

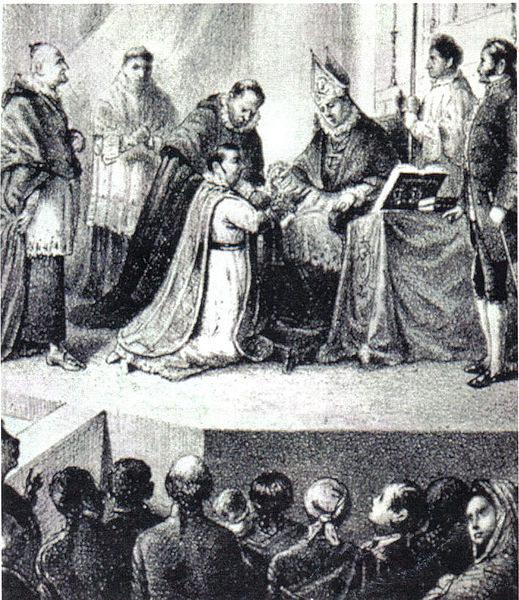

Standing before them, on November 27th, 1815, Morelos was charged with violating celibacy and fathering three children. He didn't deny it. He was defrocked and excommunicated, but there was one special torture reserved for him, which hadn't happened to either Hidalgo nor Matamoros. Morelos was made to kneel, while the areas of skin, which had been touched by holy oils at his ordination, was scraped from his body.

Three days later, Morelos was taken to at San Cristobal Ecatepec, north of Mexico City. The village had a large indigenious population. It was thought that executing him there would send a louder message to the remaining insurgents, than doing it in Mexico City. On November 30th, 1815, Morelos was shot dead by a firing squad.

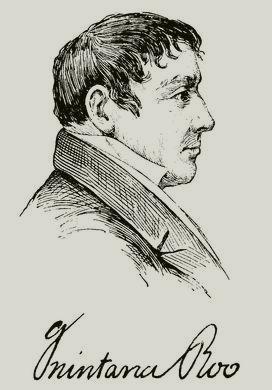

Nicolás Bravo went on to fight valiantly for independence, until 1817, when he too was captured. However, he wasn't executed, but was imprisoned until 1820. Upon gaining his freedom, he immediately resumed his activities in the insurgency. He was there, in 1821, when Mexico finally gained her independence. Later on, Bravo served three terms in office, as the President of Mexico. He died, aged 68, at his family's farm, in Chilpancingo.

Nicolás Bravo

Where to Visit:

* Chilpancingo de los Bravo, Guerrero. Previously known as Chilpancingo, the 'de los Bravo' was added in honor of the Bravo family. It's also commonly called Ciudad Bravo (Bravo's city). Nicolás Bravo was born there, September 10, 1786. The house of Los Bravos is a popular tourist attraction there.

* Acapulco, Guerrero. Morelos's army attacked and burnt down the city in 1810. The Fort of San Diego contains a museum, with a War of Independence exhibition. On the waterfront, near to the cathedral, is a monument to several heroes of the insurgency, including Morelos.

* Cuautla, Morelos. Morelos and his troops were trapped in this city for nearly three months, in 1812. The city's formal name is now La Heroica e Histórica Cuautla de Morelos (The Heroic and Historical Cuautla of Morelos), in honor of the event. The Morelos Museum, in the city, contains many items from the War of Independence, as well as exhibtions detailing the struggle.

* San Cristobal Ecatepec de Morelos, State of Mexico. This is the city where Morelos was executed. A monument stands at the spot where it happened. The house in which he stayed is now a museum, Museo Casa de Morelo (Morelo's Museum). The 'de Morelos' was added to the name of the city, in 1877, in his honor.

It was October, 1810. One of Valladolid's Roman Catholic priests was appalled. He had in his hand the proclaimation that he was supposed to read out to his congregation. It was the excommunication of Padre Hidalgo and a damning condemnation of the cause of the Army of the Americas, as issued by the Bishop of Michoacán, Manuel Abad y Queipo. Padre Morelos, sitting in his church, did not want to speak this to his parish. He didn't agree with it. It wasn't right!

It was October, 1810. One of Valladolid's Roman Catholic priests was appalled. He had in his hand the proclaimation that he was supposed to read out to his congregation. It was the excommunication of Padre Hidalgo and a damning condemnation of the cause of the Army of the Americas, as issued by the Bishop of Michoacán, Manuel Abad y Queipo. Padre Morelos, sitting in his church, did not want to speak this to his parish. He didn't agree with it. It wasn't right!

As a parish priest, in San Agustín, Carácuaro, Padre Morelos had met Brigida Almonte. The couple didn't bother to hide their relationship. He'd even took her with him, when he crossed the river to take up the parish of Nocupétaro.

As a parish priest, in San Agustín, Carácuaro, Padre Morelos had met Brigida Almonte. The couple didn't bother to hide their relationship. He'd even took her with him, when he crossed the river to take up the parish of Nocupétaro.

Leona Vicario was a wealthy woman. She had been born, in Mexico City, on April 10th, 1789, as an heiress to a Creole fortune. Her full name was Maria de la Soledad Camila Leona Vicario Fernandez de San Salvador and Montiel de Quintana Roo, which possibly explains why she introduced herself as merely Leona Vicario.

Leona Vicario was a wealthy woman. She had been born, in Mexico City, on April 10th, 1789, as an heiress to a Creole fortune. Her full name was Maria de la Soledad Camila Leona Vicario Fernandez de San Salvador and Montiel de Quintana Roo, which possibly explains why she introduced herself as merely Leona Vicario.  He was born Eligio Andrés Quintana Roo, on November 30th, 1787, in Mérida, Yucatán, as the son of José and Maria Ana Matías Quintana Roo.

He was born Eligio Andrés Quintana Roo, on November 30th, 1787, in Mérida, Yucatán, as the son of José and Maria Ana Matías Quintana Roo.

They were seeking to create an government and a declaration of independence was already being drafted.

They were seeking to create an government and a declaration of independence was already being drafted.